Ever since President Lyndon Johnson launched a set of domestic programs aimed at ending poverty and racial injustice, as a nation we have tried to reduce (if not eliminate) poverty, homelessness, and disenfranchisement. Those domestic programs range from the Food Stamp Act of 1964, the Social Security Amendments of 1965 (which created Medicare and Medicaid), and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 and Head Start, to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Taken together, these programs made up much of Johnson’s War on Poverty and his Great Society vision for the U.S.’s future. All these laudatory and equitable acts were and are essential to our democracy and overall prosperity as a nation.

Ever since President Lyndon Johnson launched a set of domestic programs aimed at ending poverty and racial injustice, as a nation we have tried to reduce (if not eliminate) poverty, homelessness, and disenfranchisement. Those domestic programs range from the Food Stamp Act of 1964, the Social Security Amendments of 1965 (which created Medicare and Medicaid), and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 and Head Start, to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Taken together, these programs made up much of Johnson’s War on Poverty and his Great Society vision for the U.S.’s future. All these laudatory and equitable acts were and are essential to our democracy and overall prosperity as a nation.

However, hidden within these programs were regulations creating consequences and barriers that prevent many people from finding a bridge out of poverty. This is the negative impact of the “benefits cliff effect.”

What is the benefits cliff effect?

A benefits cliff is what happens when public benefit programs taper off or phase out quickly when household earnings increase. The abrupt reduction or loss of benefits can be very disruptive for families because even though household earnings increased, they usually have not increased enough for self-sufficiency.

The cliff effect happens to workers near the poverty line who are eligible for a variety of programs (e.g., food stamps, Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), and subsidized public housing). The working poor reach a point where a one-dollar increase in their hourly wage can result in a significant reduction in benefits. The outcome is that the added dollars will not make up for the loss of food stamps, childcare, or other benefits designed to help people in poverty or near poverty.

The steep reduction in benefits can discourage people from engaging in workforce development programs or from even seeking employment in the first place. Many people in poverty rely on a combination of earned income, public benefits, and community supports to survive. When these resources are unpredictable, people in poverty inevitably must choose which necessities they will not buy. Inconsistent access to nutritious food, medical care, safe housing, and childcare has detrimental effects on health and well-being.

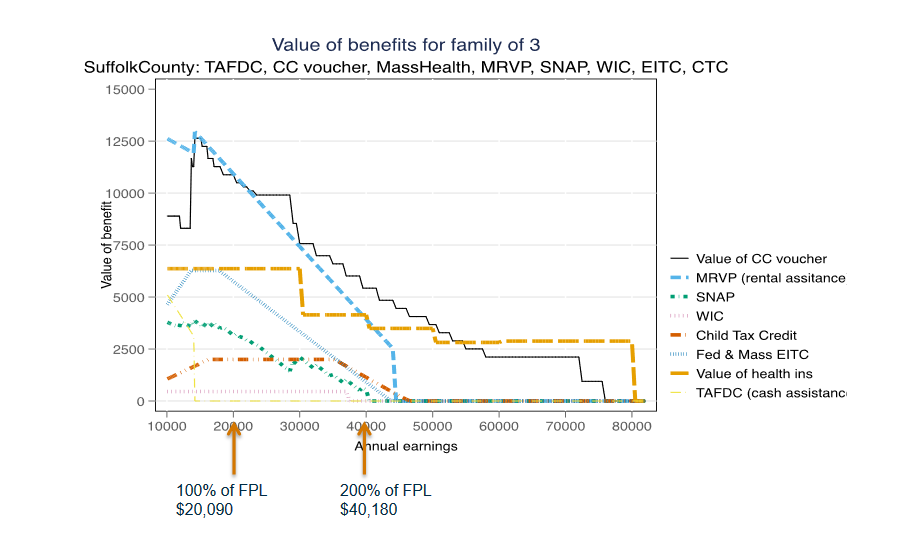

Here is an example of the benefits cliff from the Center for Social Policy, University of Massachusetts, Boston. This graph shows a situation where a higher income actually means fewer resources overall:

For even more on cliff effects, visit the Center for Social Policy’s website.

For even more on cliff effects, visit the Center for Social Policy’s website.

The chart illustrates the dilemma of the benefits cliff. Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour ($30,000 per year) wouldn’t necessarily solve the problem. The regulations and the administration of public benefits are where the problem lies.

Yes, we must work to increase minimum wages and advocate for salaries that allow families to thrive, not just survive. But just as important as helping these families become self-sufficient is finding ways to mitigate, or better yet end, the negative impact of the benefits cliff. This has to happen if we are to reinforce and sustain the effectiveness of our poverty reduction initiatives.

What can states do about the benefits cliff?

We must consider the gradual reduction of benefits as salaries increase, turning the cliffs into slopes, which would allow families to become self-sufficient over time.

There are states across the country that have taken steps to lessen the precipitousness of the cliff effect. For instance, according to this article from The Aspen Institute:

- Colorado’s Child Care Assistance Cliff Effect Pilot Program, most recently revised in 2016, is designed to “develop a revenue-neutral approach for each family as income rises. Evaluation efforts have sought to determine if the parents in the pilot program changed their behaviors to be more likely to accept promotions, work additional hours, and take higher paying jobs, all of which would result in increased income.”

- In 2017, Maryland’s Governor’s Executive Order 01.01.2017.03 created the Two-Generation Family Economic Security Commission and Pilot Program. Maryland’s pilot program mandates the linkage of programs and services to create opportunities and address families’ and children’s needs with a specific focus on early-childhood education, elementary education, economic stability, and family engagement.

If we are to end generational poverty, we must encourage more states to adopt a two-generation approach that focuses on forging opportunities to address needs of both children and adults. To understand the benefits cliff effect more fully, we must also investigate self-sufficiency.

The most precise definition of self-sufficiency is the income level a family requires to meet their basic needs without public assistance. Many states are seeking ways to enhance and accelerate self-sufficiency by addressing the negative impact of the benefits cliff. These states have created self-sufficiency calculators that alert social services staff and their customers when income thresholds could cause an abrupt reduction in services. These states have also set the income thresholds where self-sufficiency begins.

Other states have set up or changed programs and regulations to reduce the negative impact of the cliff effect related to TANF:

- Increasing the threshold on assets tests or completely ending the assets test so families can open savings accounts. Alabama, Maryland, Ohio, and Virginia are four states that have completely done away with assets tests.

- Some states do not count vehicles as assets when calculating who is eligible for benefits.

- Arizona and six other states do not count child support benefits when determining which families are entitled to TANF.

- New York allows one automobile up to $12,000 fair market value. Furthermore, in the case of automobiles equipped for individuals with a disability, the equipment is not considered to increase the value of the vehicle.

These essential incremental steps are not enough; we need to do more to create a bridge out of poverty. The following remedies are steps in the right direction:

- Align eligibility determination procedures, documentation requirements, and timelines across programs so that people do not lose all their benefits at once.

- Gradually decrease benefits over a period of at least one year.

- Establish reasonable time frames for reporting changes in income, and adjust regulations that will treat income from distinct types of employment differently in the benefit-determination calculations. For example, assessing overtime and temporary jobs individually so as not to penalize people unfairly.

- Provide warnings, and conduct benefit-adjustment hearings before sanctioning a recipient for potential noncompliance with program requirements.

- Fund “benefits transition navigators” who will help individuals find and access all the public benefits and community-based supports available to them. In addition to case management, information, and referral services, the navigators can help people understand options and consequences when balancing benefits, income, and community or social network supports.

- Conduct research on the effectiveness of coordination, as well as other “cliff effect interventions,” to provide quantitative evidence about cost efficiencies for programs and improved services and outcomes for individuals.

- Support the creation of a cross-agency “benefit coordination blueprint.” This blueprint would help train program staff at the local level. It could also guide investments in technology and infrastructure to connect, as appropriate, data and information systems.

What can employers do about the benefits cliff?

Employers can help reduce the benefits cliff by educating themselves on the trade-off between employment and benefits, then create solutions for barriers to getting and keeping jobs. Concerned employers might consider the following:

- Dealing with social services agencies takes up a lot of time. Employers can work to accommodate time off or adjust schedules for employees to attend benefits hearings and otherwise troubleshoot coordination of government benefits.

- Network with other employers to help workers access childcare and other social supports.

- Bring Success Coaches from the Employer Resource Network on site to aid employees with wraparound services on an ongoing basis.

What can community and faith-based organizations do about the benefits cliff?

Community-based and faith-based organizations are often the first line of defense and are increasingly the informal safety net for persons suffering economic hardships. While regularly overburdened with providing services, these entities can help address the cliff effect in the following ways:

- Supplement “benefit transition navigators” with a mobile “211” service that goes into neighborhoods to improve the availability of exact information about services and supports.

- Educate workforce development programs and employers about the barriers low-wage workers confront when taking part in education and training and about the trade-offs between meeting immediate needs and seeking socioeconomic advancement through employment.

- Facilitate collaboration across programs that serve low-wage workers.

- Support the continuation of task forces comprising members from public and private sectors, as well as state and local government agencies. The task forces should examine the range of issues affecting working persons in poverty, develop strategies to help them, and monitor the outcomes.

Poverty is intersectional, has many causes, and needs coordinated and sophisticated solutions, among which is reducing the cliff effect.

Why should we do anything at all about the benefits cliff?

The reason is straightforward: Families can find a bridge to economic self-sufficiency. Employees experience economic security for their children even when accepting raises, working overtime, and accepting promotions, and this makes them more likely to stay employed. This strategy will also help employers reduce the high cost of employee turnover.

A coordinated and collaborative effort by government, businesses, community- and faith-based organizations, and the people themselves can create pathways to sustainable and actual reduction in poverty rates. Such efforts will increase economic stability, reduce dependency on the government, improve child and family outcomes, and support economic development for the entire community.

Pedro Perez is committed to social justice and equity. He helps people in poverty gain access to education, sustainable employment, and entrepreneurial opportunities, exemplifying his commitment to equity and social justice. Dedicated to helping those living in poverty, Pedro strives to ensure diversity and inclusion are priorities for every organization with which he works. He rose to the rank of brigadier general in the New York State Police and served as acting superintendent during Governor Spitzer’s and Governor Paterson’s administrations. Pedro made New York State Police history by becoming the highest-ranking Afro-Caribbean Taíno Indian. Throughout his nearly 30-year tenure with this statewide policing agency, he advocated assertively and helped actualize for greater inclusion of minority men and women within its ranks.

Pedro Perez, Project Director at the City of Albany Poverty Reduction Initiative, chats about growing up in poverty, the cliff effect and what it takes to build a bridge out of poverty.