In 2018, aha! Process published a two-part blog series titled “The road to responsibility,” written by David Burgess, a retired principal with Henrico County Public Schools (Virginia), adjunct professor at the University of Richmond, and university supervisor at James Madison University. Burgess recently wrote to aha! Process: “I think the reasons for the blog have actually increased since 2018. The fact that you are using and publishing the book Before You Quit Teaching kind of says it all.”

Burgess makes two important points: “When misbehavior occurs, students from poverty learn how to take responsibility for their own behavior, which starts with a step-by-step problem-solving process and a specific plan; and students learn, practice, and use communication skills, which readies them for the middle class world they will be entering.”

The two-part blog was timely in 2018, and it is just as timely now. That’s why aha! Process decided to republish it, as its ideas and insights are more relevant than ever. Read below to find out more about “The road to responsibility.”

Part 1

The road to responsibility: School suspensions are out of control—what to do about it

Out-of-school suspensions are increasing, disproportionately unbalanced, and they don’t work to change behavior in most instances. How big is the problem? In 2016 the U.S. Department of Education reported that 3.45 million (of the 50 million students who attend public schools) were suspended out of school. And 130,000 students were expelled. Further, they noted, “Various data sources show clearly that students with disabilities and students of color are disproportionately impacted by such practices…black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students, while students with disabilities are twice as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension as their nondisabled peers.” Many of these students live in poverty.

Out-of-school suspensions are increasing, disproportionately unbalanced, and they don’t work to change behavior in most instances. How big is the problem? In 2016 the U.S. Department of Education reported that 3.45 million (of the 50 million students who attend public schools) were suspended out of school. And 130,000 students were expelled. Further, they noted, “Various data sources show clearly that students with disabilities and students of color are disproportionately impacted by such practices…black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students, while students with disabilities are twice as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension as their nondisabled peers.” Many of these students live in poverty.

How did this shocking state of affairs get this way, and what can be done about it? What are specific, long-term positive practices, not restorative practices that are essentially remedial and of short-term benefit?

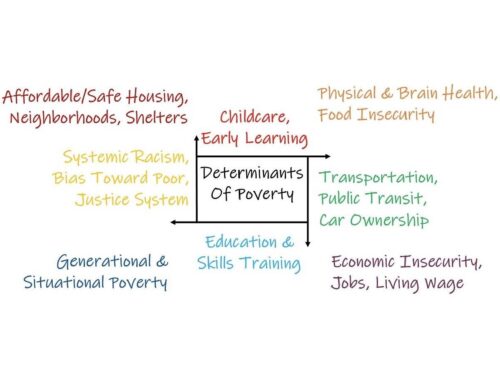

First, some background on what underlies misbehavior so egregious that a student must be suspended (often multiple times) out of school. One large contributor to this state of affairs is an overwhelming issue that impacts millions of school children every day: They live in poverty. For the most part they lack adequate food, housing, and interaction with positive role models. Dr. Ruby Payne is an acknowledged expert on poverty and schools, and in her seminal book she sheds a bright light on what contributes to children from poverty having difficulty with school rules.

The majority of schools in the U.S. reflect the larger socioeconomic focus on middle class values and ways of interaction. In the middle class one has to understand the abstract world of concepts and ideas. Conversely, those living in poverty are at the survival level of life. Going hungry is not an abstract concept. Moreover, thousands of public schools are staffed by middle class teachers who uphold middle class rules. Schools are about the future, while poverty is about surviving today. Sounds okay if you’re in the middle class. But what if you aren’t?

What is it about living in poverty that contributes to students not following middle class rules in the schools? Payne outlines three issues that come into play. The first is how punishment for misbehavior is handled in poverty. Basically, in poverty, discipline is a cycle of misbehavior, penance, and forgiveness. That is, if children show penance for their actions, this leads to forgiveness from adults. Little thought is given to the behavior repeating/escalating. Violence is also often present, and “penance” is a result of coercion. But in the middle class world of the school, misbehavior is about changing one’s behavior so that misbehavior is not repeated. The emphasis is on learning from one’s mistakes. Most school teachers were raised in and live in the middle class. So for students from poverty, the way they are disciplined at home conflicts with what public school expects in the way of following rules.

A second issue is what Payne calls “hidden rules.” She notes that any subgroup (as well as the three broad social classes of poverty, middle class, and wealth), has unspoken cues and habits that are unknown to those from outside that group. At best, students from poverty are at a disadvantage in a middle class environment; it is as foreign to them as the world of poverty would be to a middle class kid.

A third issue that really speaks to how one is raised in a middle class household is what Payne calls “the language of negotiation.” She outlines the difference between processing problems with the “child voice” (feeling helpless), the “parent voice” (judgmental, win-lose mentality), and the “adult voice” (open, nonjudgmental, win-win problem solving). Payne states there is not much negotiation in poverty since one doesn’t have many options over which to negotiate. So when teachers, using the parent voice, evaluate behavior they believe violates a rule (a rule that perhaps the child did not understand), the child might laugh inappropriately. This makes teachers feel disrespected. When I was a principal, students showing disrespect was always the main reason they were referred to me.

The conundrum, of course, is that preparing students to join the world of work is a primary goal of education, and the world of work operates on middle class norms too. But for many kids in poverty, being exposed to middle class norms in schools doesn’t “take.” Further, students who are seen as disrespectful and who don’t have the skills to succeed in school rob others of learning, as well as doom themselves to a lifetime of being behind. To add irony to injury, schools too often suspend these students out of school, sending them back to the very same environment that doesn’t understand or foster compliance with school rules in the first place.

So what can actually be done? There are preventive approaches that work in public schools. In the next blog post I will share what I have used that teaches students from poverty how to generate alternatives—and make choices—that keep them in school and learning. In my school we treated misbehavior as a teaching opportunity for students to learn to problem solve with people. This is a long-term approach that actively teaches children the communication skills they need to be successful in school—not suspended out of school.

Part 2

The road to responsibility: Teaching responsibility skills

Before I proceed with this revolutionary blog post, I  want to say that I have used the ideas and taught the skills I reference. But what is new and exciting is the idea to combine the two approaches—they complement each other. The key to success is to use both approaches, consistently, every day.

want to say that I have used the ideas and taught the skills I reference. But what is new and exciting is the idea to combine the two approaches—they complement each other. The key to success is to use both approaches, consistently, every day.

My first preventive practice is really an intervention: It’s based on what shouldn’t be a revolutionary idea: Treat misbehavior as a problem; a problem to be solved—not a chance to punish and then expect a change in behavior. I got this idea from William Glasser’s book Choice Theory. Glasser was a giant in psychology and schools.

I call the approach Time Out for Problem Solving (TOPS). Initially, when misbehavior occurs, the teacher asks:

“What were you doing when the problem started?” (Teacher guides the student to label what the student did.)

“Was that against the rules?” (Rules have been taught early on and are known by all students.)

“We have a problem: My job is to teach, and yours is to learn. Can we work it out so this doesn’t happen again?”

If the student responds inappropriately in any way, the student is sent to the office or TOPS area. “If you won’t follow our rules, you are choosing to leave the class.”

In the TOPS area, an individual (school counselor and/or individual trained in active listening) will take the child through a simple, five-step problem-solving approach that reflects the feelings behind the behavior and explores options. The student is not summarily dumped in a room for in-school suspension. Rather, the student must make a plan to correct the problem the student has caused (take responsibility for actions), and the student won’t be allowed back into the classroom until the teacher approves the plan.

And what about the plan itself? To paraphrase Payne, if individuals cannot plan, they cannot predict, identify cause and effect relationships, or identify consequences—all of which contribute to controlling impulsivity. Ultimately, if one cannot control impulsivity, this inclines one “toward criminal behavior.”

Of course, the individual in charge of TOPS may call the parent and/or provide a consequence. With exceptions for extreme misbehavior, the first choice is not an out-of-school suspension. As a principal I did not have space for a TOPS room, but I did treat misbehavior as a problem to be solved. And I almost never suspended out of school (fewer than 10 times per year for four or five students, and then usually for one day only). And when I did suspend students out of school, it was a punishment but rarely worked to change behavior.

The second preventive practice is Character Education Skills for Students (CHESS).

The key to this approach is to hold class meetings on a daily basis—a minimum of 15 minutes for grades K–2 and 30 minutes for grades 3–5. Meetings are conducted by the teacher. Just being in a circle teaches that everyone is important. This daily interaction wherein the teacher teaches communication skills fosters building a classroom community and a positive relationship of respect between teacher and students.

Moreover, as the year proceeds, the class comes to develop their own norms of behavior—positive peer pressure becomes a fact of life that reinforces the classroom’s rules. In other words, it’s not just the school’s rules; it’s now our classroom rules—The Way We Do Things.

Moreover, as the year proceeds, the class comes to develop their own norms of behavior—positive peer pressure becomes a fact of life that reinforces the classroom’s rules. In other words, it’s not just the school’s rules; it’s now our classroom rules—The Way We Do Things.

Consistency is always the key with discipline; this is also the case in developing self-discipline and learning responsibility. In a CHESS classroom, daily proactive negotiation and communication/problem-solving skills are taught and practiced; students experience the give-and-take of human interaction; students learn it’s okay to be different from others. Of course, the teacher also reinforces students verbally as the teacher sees them using negotiation/communication skills throughout the school day. Students are constantly learning that choices always have consequences.

Specific skills are taught and used, including listening (how to attend and show you’re paying attention to another person); how to ask open questions; how to paraphrase, clarify, and summarize what others are saying; and much more. These are skills that demonstrate respect for others. How so? Truly open questions (who, what, where, when, how, and why) are nonjudgmental. The goal of an open question is to learn information—to open a conversation, not find a right answer. Teachers also learn that they may not agree with what a student may say, but you don’t start a conversation with a closed question. But be careful when asking why: It can make a child defensive. Which question would you better respond to: How did that happen? or Why did you do that?

So what do these two interrelated practices, fully implemented, need to be successful? How would these two approaches look in a school that was committed to (1) treating misbehavior as an opportunity to teach problem-solving and (2) building class communities in which students learn communication and problem-solving skills and how to be responsible citizens?

You would need four components and a mindset:

- Time scheduled every day to teach and practice communication skills and build community in classrooms in morning meetings. I recommend a school/school district pilot this program and begin with teachers interested in trying the concepts.

- TOPS room/dedicated space for the problem-solving/planning process to take place.

- School counselor (or an individual trained as a nonjudgmental listener) to staff a TOPS room that is always open. The process requires the listener to meet with the child and guide the child through the two processes: problem-solving and planning. It’s not a holding room.

- Teacher training: Nonjudgmental listening and questioning skills on the part of teachers is essential to building trusting relationships and teaching communication skills in CHESS daily meetings. This is different from asking academic questions with the emphasis on one right answer.

- Growth mindset: Parents/guardians of students from poverty mean well; they love their kids, but they are at the survival level of life and for many reasons often don’t give their children skills and understandings they need to succeed in school. They need help that the schools can provide.

Long-term benefits: The administration (school or district level) must be committed to implementing with fidelity steps 1–4. In the larger sense, implementing both practices—and reducing out-of-school suspensions—will not only increase learning but also reduce the need for (and cost of) remediation (which is always expensive). Another long-term outcome is improved teacher morale and less turnover of teachers.

As noted above, I suggest any interested school start with a small pilot for a year and learn from the implementation, compile data, and gain parental (and student) feedback and support. It’s always easier to build upon success.

But why do you need both TOPS and CHESS? To create synergy!

The CHESS approach is developmental and daily; communication and problem-solving skills are taught and used every day. And if a child is sent to the TOPS room, the skills used and reflection of feelings there will be consistent and the same. Recall that if a child must be sent to the TOPS room, the class norms (not just the middle class teacher’s norms) have been disrespected when this happens. Offenders want to rejoin the class in which they feel respected, not ostracized. They also learn what a plan is and—this is critical—there’s often little planning in poverty. Students learn how to plan and generate alternatives and possible consequences of their actions.

In summary, out-of-school suspensions are pervasive, punitive, expensive, and obviously are not working to change behavior. We cannot suspend ourselves into what we want public schools to be for all students. It’s time to look at how to teach responsibility skills (problem-solving and communicating) as a viable alternative to most suspensions; time to give teachers the tools to build responsibility in all their students; time to spend a few minutes a day to teach strategies and foster positive student interaction among all students; time to admit too many students at home are not learning to learn from their mistakes.

I have briefly outlined two interrelated ways that students from poverty can experience positive relationships with the teacher and classmates and build community in their classrooms. When serious misbehavior occurs, students will be listened to and guided to make a plan they are responsible for implementing in the classroom. Except for extreme misbehavior, the need for out-of-school suspensions is all but eliminated.

Of course, there is a place for out-of-school suspensions as a last resort, and tutoring can make a difference with weak/missing academic skills. But what schools with high-poverty populations are desperate for are students who want to be there—who respond to high expectations with the best they can give.

When a student who used to be in trouble too often, who was even suspended out of school, learns how to solve communication problems with others, learns how to learn from mistakes, realizes that school is a place to feel good about, and sees there’s a reason to follow the rules and work hard every day, then that student is truly on the Road to Responsibility.

I wonder what the cost of implementing these preventive practices would be in comparison with all the thousands of dollars and hours spent on remediation?